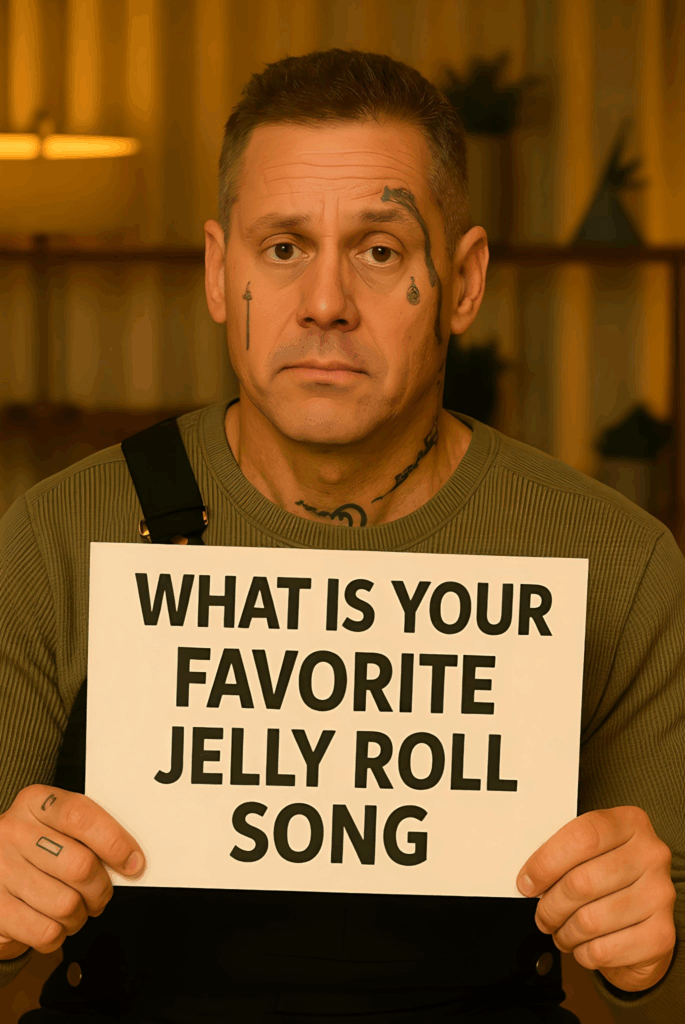

Mtp.The Goodbye Jelly Roll Could Only Write in a Song

How a Silent Notebook Page Became the Most Important Verse Jason DeFord Ever Penned

Nashville, November 29, 2025

Before the sold-out arenas, before the CMA tears, before the 170-pound resurrection and the crossover coronation, Jelly Roll was just Jason from Antioch: big kid, bigger scars, bigger dreams he didn’t yet know how to hold.

And there was one man who saw it all and never blinked.

His name was David, a grizzled local producer who ran a tiny studio out of a converted garage on the east side of Nashville. No plaques on the wall, just cigarette burns on the console and a sign that read “Truth or GTFO.” In 2009, when Jason was 25, fresh out of his last prison stint and sleeping on couches, David caught him freestyling in a cypher behind a laundromat. Instead of walking away, he pressed a crumpled twenty into Jason’s hand and said, “Come to the studio tomorrow. Bring the real shit, not the street shit.”

Jason showed up with a spiral notebook full of half-rhymes and half-lies. David listened to one take, shook his head, and slid a Shure SM7 across the table. “That ain’t you, bruh. That’s what you think they want. Rap what’ll still be true when you’re fifty and fat and nobody’s listening anymore.” Then he hit record and walked out of the room.

Something cracked open that night. Over the next three years, David became the only constant in a life that still felt like a revolving door: court dates, overdoses, relapses, break-ups. When Jason wanted to quit, David locked the studio door and made him finish the verse. When Jason wanted to chase radio, David played him old Johnny Cash and said, “Real don’t chase. Real waits.”

By 2017, the calls started coming: labels, managers, people with money who spoke in futures and percentages. Jason’s demos (rough, bleeding, honest) were suddenly worth something. Meetings in glass offices. Promises of tours, buses, bright lights. Every yes pulled him further from that garage studio and the man who’d handed him a mic when nobody else would.

One night, after a particularly glossy pitch meeting, Jason drove back to Antioch with a knot in his throat he couldn’t swallow. He sat in David’s driveway until 3 a.m., too scared to knock. Instead, he opened the glovebox, pulled out the same spiral notebook from 2009, and wrote the hardest page of his life:

If I stay where I started I’ll never become who I’m meant to be. You gave me the match. Now I gotta walk into the fire you lit. This ain’t running away. This is finally running toward. Thank you for seeing the man before I was brave enough to be him. I love you. I’m sorry. Goodbye.

He tore the page out, folded it once, and slid it under the studio door.

The next morning David found it. He didn’t call. Didn’t text. Just left a single Post-it on Jason’s windshield when he came back to pick up his hard drive:

“I already knew. Go be great. Door’s always open when you need to remember who you are.”

Jason drove away crying so hard he had to pull over on Bell Road.

That notebook page never became a song lyric (some goodbyes are too sacred for stages). But every time Jelly Roll steps in front of 20,000 people and sings “Son of a Sinner” or “Save Me,” every time he talks about grace he didn’t deserve and redemption he still doesn’t understand, that folded piece of paper is pulsing underneath the words.

Years later, when he was finally big enough to buy David a proper house, he tried. David laughed, handed the deed back, and said, “I don’t need a mansion, kid. I just need you to keep telling the truth.”

So Jelly does.

And somewhere in East Nashville, in a little garage studio that still smells like stale Newports and hope, an old producer keeps a single spiral notebook page taped above the mixing board.

It’s creased and faded now, but you can still read every word.

Some goodbyes aren’t spoken out loud. Some are written in the margins of the life you were brave enough to leave behind, so you could become the man someone once believed you could be.

That’s the realest verse Jelly Roll ever wrote. He just never put it on a record. He lived it instead.