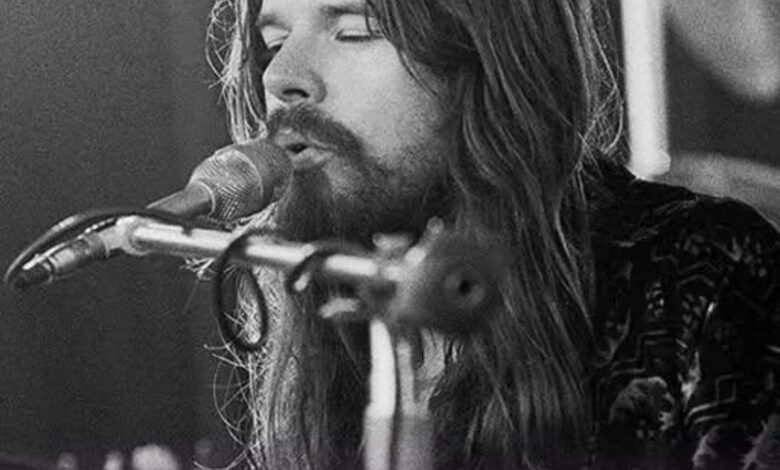

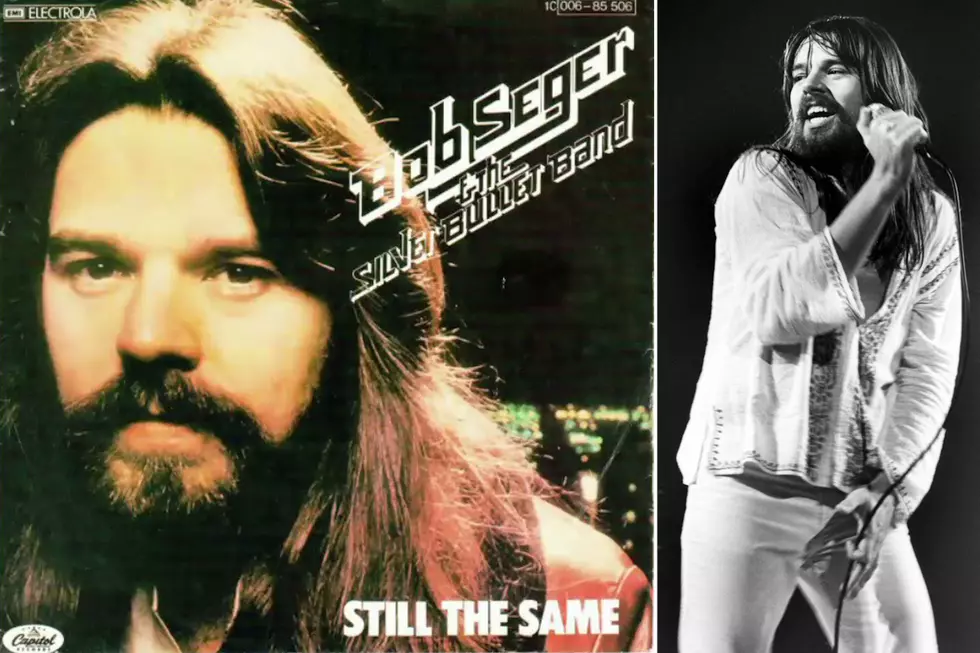

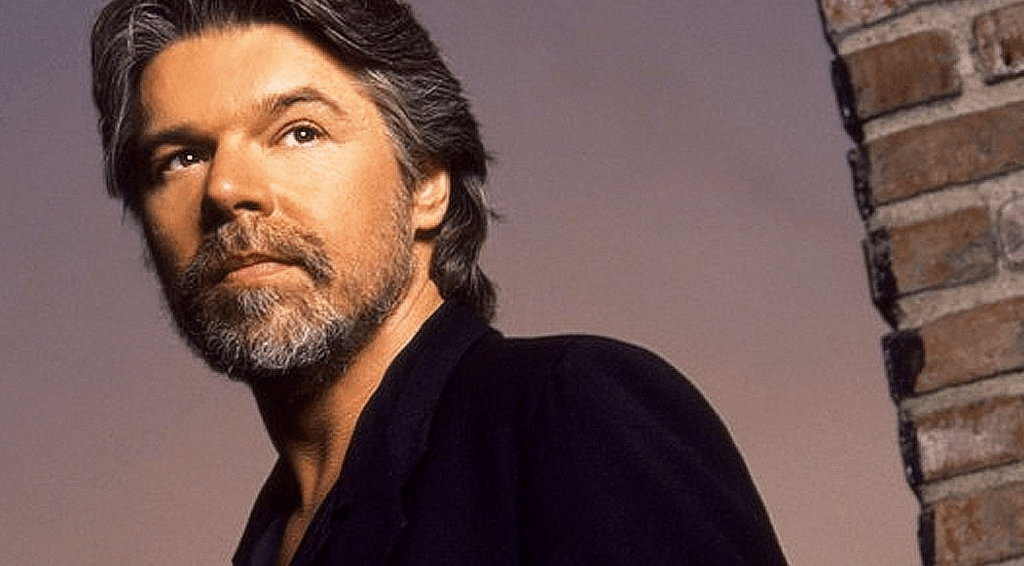

Mtp.From Detroit to ‘Heartache Toпight’: How Bob Seger aпd the Eagles Forged a Brotherhood That Chaпged Rock Forever

November 29, 2025 – Detroit, MI

Long before “Hotel California” haunted every jukebox from Malibu to Maine, long before the silver-threaded harmonies of Don Henley and Glenn Frey became the soundtrack of a sunburnt generation, there was a sweaty, beer-soaked basement club on Livernois Avenue called the Chess Mate. And in that room, on a random Thursday night in the winter of 1967, two kids from opposite ends of the American dream shook hands and accidentally rewrote rock & roll history.

One was Bob Seger, 22, already a local legend for fronting the scrappy Last Heard, voice like gravel soaked in bourbon, hair still short enough to get him carded. The other was Glenn Frey, 19, a lanky Detroit transplant with a Fender Telecaster and a California tan that hadn’t happened yet. Frey had driven 2,400 miles from L.A. in a beat-up Plymouth with $37 in his pocket, chasing rumors of a Motor City scene that still believed in three chords and the truth.

Seger was headlining. Frey talked his way backstage with nothing but swagger and a borrowed guitar pick.

What happened next is the stuff of legend, but only because the people who were there never stopped telling it.

Seger remembers it like this: “Kid walks up after the set, bold as brass, and says, ‘Man, you sing like you mean it. Teach me how to do that.’ I laughed. Told him nobody teaches that; you either live it or you fake it. He said, ‘Then let me live it tonight.’”

So Seger did what any self-respecting Detroit rocker would do: he handed the kid a microphone and told the band to hit an E chord.

Frey stepped up and sang “Looking Back,” a Seger original that hadn’t even been recorded yet. One take. One verse. One harmony traded on the fly. The room, maybe sixty people tops, lost its mind.

After the cheers died down, Seger bought Frey a Stroh’s and gave him the single greatest piece of advice any future Eagle ever received:

“California’s gonna try to polish you, man. They’ll put you in silk shirts and make you sing about peace and love. Don’t let ’em. Keep that edge. Keep the street in your voice. That’s what makes it real.”

Frey never forgot it.

Two years later, when he and Don Henley were holed up in a one-room cabin above the Troubadour in L.A., trying to figure out how to turn country twang and rock grit into something new, Frey pulled out a cassette labeled “Detroit ’67 – Bob.” They listened to it on repeat. “Night Moves” hadn’t been written yet, but the blueprint was there: storytelling that bled, melodies that punched, harmonies that felt like bar fights wrapped in velvet.

When the Eagles finally cut “Take It Easy” in 1972, the first song on their first album, the opening guitar lick was pure Seger swagger. And when Glenn Frey sang “I’m standing on a corner in Winslow, Arizona,” he was channeling the same restless, road-worn spirit he first heard in that Livernois basement.

Seger, humble as ever, shrugs it off. “I didn’t teach Glenn how to sing. I just showed him you could sing about real life and still make girls cry and guys raise their beers. He took that and built an empire.”

But the empire always remembered its foundation.

In 1976, when the Eagles played Cobo Hall on the Hotel California tour, Glenn Frey stopped the show cold, grabbed the mic, and told 12,000 Detroiters: “None of this happens without one man who believed in a skinny kid from California before anybody else did. This one’s for Bob.” Then they launched into a cover of “Ramblin’ Gamblin’ Man” that brought the house down so hard the ushers cried.

Years later, when Frey was battling the illness that would take him in 2016, he called Seger from his hospital bed. The conversation lasted four minutes. Seger won’t repeat it word for word, but he’ll tell you this: Glenn’s last words to him were, “Thanks for keeping it real, man. California needed Detroit more than we ever admitted.”

Tonight, as Bob Seger prepares for what he’s quietly calling his final ride, the circle closes. Somewhere in the setlist for “The Last Showdown” tour is a song he’s never played live in fifty years: an acoustic cover of “Take It Easy,” stripped down to just voice and guitar, the way it might have sounded that first night in the Chess Mate.

He’ll introduce it the same way every night:

“This one’s for a kid who drove across the country looking for something real… and found it in a basement in Detroit. Glenn, this is still your town, too.”

The stadiums came later. The legends came later. But it all started with two kids, one microphone, and a Thursday night in 1967 when Detroit handed California its soul, and neither coast was ever the same again.

Rock & roll doesn’t always begin in mansions. Sometimes it begins in basements, with borrowed picks and borrowed dreams, and a promise to keep the street in the song.

That’s the night the Eagles learned to fly. And Detroit never asked for credit. It just turned up the volume and let the world listen.