kk.AFTER 5 WEEKS, TATIANA SCHLOSSBERG DIDN’T JUST SHARE HER DIAGNOSIS — SHE SHATTERED THE SILENCE SYSTEM BUILT AROUND CAROLINE KENNEDY’S GRIEF

When the news broke that Tatiana Schlossberg had died at 35, the first thing many people remembered wasn’t a headline. It was her own voice—measured, intimate, and unavoidably human—because she had already told the world what she was afraid of.

Not only of dying.

She feared becoming one more loss her mother would have to carry.

Of what her diagnosis would do to her mother, Caroline Kennedy.

That detail is what makes this story land like a bruise. Tatiana didn’t write about illness as a distant medical storyline. She wrote about family as a living system—how one person’s pain becomes everyone’s weather, and how love can make you feel responsible for storms you didn’t create.

Weeks before her death, Tatiana shared that she had been diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia. Doctors discovered it while she was hospitalized after giving birth to her second child, a daughter. The timeline alone is hard to hold in your head: new baby, postpartum recovery, and then a diagnosis that instantly rewrites the future.

Tatiana was not only Caroline Kennedy’s daughter. She was also a writer, a wife, and the mother of two young children. She married George Moran in 2017. She and George had built an ordinary kind of happiness—quiet routines, shared plans, the invisible work of raising a family—until the diagnosis turned the calendar into something frighteningly small.

In the way she described it, the cruelest part wasn’t only what was happening to her body. It was how the illness threatened to become another chapter of public grief for her mother.

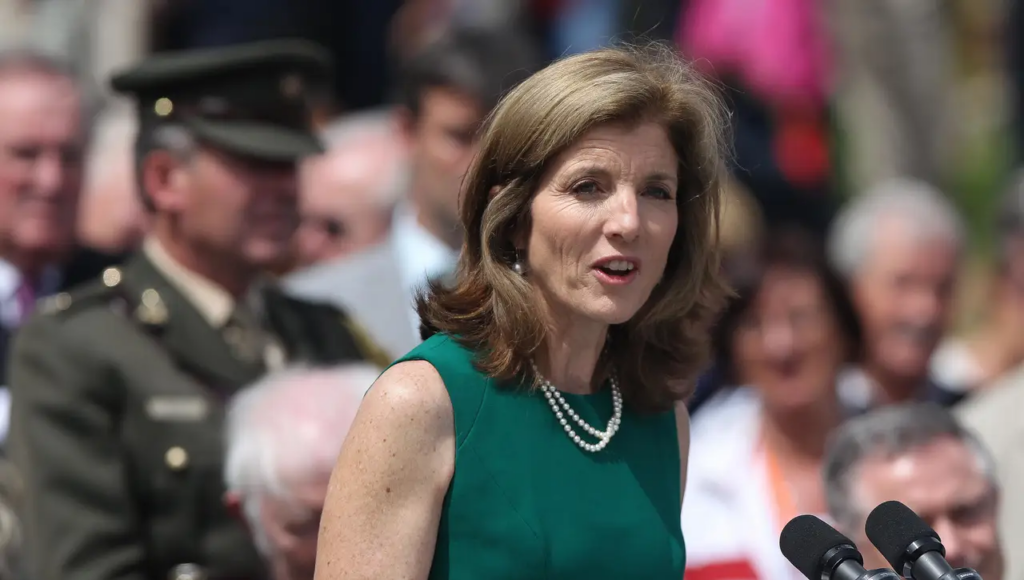

Caroline Kennedy has lived through losses that most people only know from history books: the assassination of John F. Kennedy when Caroline was just days from turning six, and the death of John F. Kennedy Jr. in a plane crash decades later. Tatiana grew up with that shadow in the background—public tragedy, private sorrow, the awareness that grief can become a family’s permanent headline even when the family desperately wants to be normal.

Tatiana seemed to carry a lifetime habit of trying to protect her mother from more pain. She wrote about wanting to be “good,” to be careful, to never become another source of heartbreak. That’s a feeling many people recognize even without famous last names: the child who grows up reading a parent’s sadness like a weather report, learning to stay quiet so the house stays calm.

But leukemia doesn’t negotiate with good intentions.

Illness doesn’t care how responsible you have been, or how gently you tried to live.

And that’s where Tatiana’s writing became unforgettable: she didn’t pretend courage meant not being scared. She let readers see fear, love, anger, and bargaining all at once—without turning it into a performance.

She wrote about George Moran with a tenderness that made people stop scrolling. She described his steady devotion and the life they had built together, and she admitted the bitter feeling of being cheated—cheated out of time, out of ordinary years, out of the future they assumed would be theirs.

Then there were the children. The part that most people can’t shake is how she faced the possibility that her kids might be too young to remember her. It’s one thing to talk about mortality in the abstract. It’s another to picture a toddler growing up with only photographs, secondhand stories, and a parent’s memory that becomes a legend instead of a daily presence.

What made people pause was the timing: Tatiana published her essay on November 22, 2025. That date matters because it means she chose to write while the outcome was still uncertain, while treatment was still underway, while her children were still new enough that the smell of their hair could feel like a lifeline. She didn’t wait for a neat ending. She wrote from inside the blur.

The writing also carried a strange tension between public and private. Tatiana was born into one of America’s most scrutinized families, yet her essay wasn’t political theater or legacy management. It read like a person trying to tell the truth before the world turned her into a symbol. In that sense, her name opened doors, but it also raised the stakes: anything she revealed would be amplified, analyzed, and repeated.

Some people have wondered—without any confirmation—whether she hesitated before publishing because she knew how quickly strangers would claim the story as their own. Others speculate that her family will keep funeral arrangements private, limiting details to protect her children and to give Caroline Kennedy a rare space to grieve away from cameras. Those ideas may never be verified, but they reflect something real: the difference between mourning as a family and being mourned as a public narrative.

And in that gap, people keep returning to her sentences, because they are the only part that feels owned.

Tatiana didn’t romanticize motherhood in crisis. She wrote about the practical theft of illness—the way treatment doesn’t just weaken you, it can separate you from the most basic acts of care. After transplants, infection risks can make the simplest things dangerous. She described how that reality forced distance right when she wanted closeness most.

And still, she tried to stay present. Not in a motivational way. In a desperate, honest way: soaking in what she could, holding on to small moments, trying to remember even as the days slipped through her hands.

Her family later confirmed her death on December 30, saying she would always be in their hearts. The public, understandably, began searching for “final words,” for funeral details, for something that would make sense of it all. But if you focus on what Tatiana chose to share, the real “final words” weren’t about arrangements or ceremonies. They were about love, and the unbearable math of time.

When people search for “funeral details,” they’re usually looking for structure: a location, a date, a program, a sense that grief can be scheduled and contained. But the most striking thing about Tatiana Schlossberg’s story is that the only real structure she offered was emotional. She described what mattered while it still mattered, and she did it with the kind of clarity that feels almost impossible at 35.

Tatiana’s essay was not a medical report. It was a map of priorities drawn under pressure. She wrote about the diagnosis—acute myeloid leukemia—arriving at the same moment life was supposed to be expanding. A new baby. A family already in motion. And then, suddenly, hospital rooms and risk calculations became part of the daily language.

One of the most arresting themes in her writing is that she kept turning away from herself and back toward other people. That may sound like kindness, but it also reads like a lifetime pattern: a daughter trained to protect her mother, a mother trying to protect her children, a wife trying to protect a marriage from a tragedy it didn’t choose.

The fear she named most plainly wasn’t, “What will happen to me?” It was, “What will this do to Caroline Kennedy?”

That is an unusually specific grief: grieving the grief you are about to cause someone else, even when you have no control over it.

Caroline Kennedy’s public history is well known. She became a symbol of national mourning as a child, and later lived through another very public loss when John F. Kennedy Jr. died. For many families, grief is private and fades into the background of ordinary life. For the Kennedy family, grief has often been public, narrated, and archived. Tatiana’s writing suggests she was painfully aware of that. She wasn’t only facing illness; she was facing the fear that her death would become another “chapter” for people to summarize.

That’s why her focus on motherhood feels so devastating. She wasn’t speaking in metaphors. She wrote about the plain, physical realities of treatment and the infection risks that follow transplants. Those risks can force separation from the most basic acts of care. She described being unable to do simple things that most parents do without thinking—changing a diaper, feeding a baby, bathing a child—because being close could be dangerous.

In a few sentences, she exposed an uncomfortable truth about serious illness: it doesn’t only threaten your life, it can interrupt your identity. Motherhood is built on touch, repetition, and small routines. Treatment can turn those routines into forbidden territory.

Tatiana also wrote about her children in a way that was both loving and unsentimental. She acknowledged the possibility that they might not remember her clearly. That is a thought that most parents push away because it’s too sharp to hold. She didn’t push it away. She looked at it directly, and she wrote from inside that pain.

At the same time, she wrote about her husband, George Moran, with a kind of gratitude that feels heavy because of what it implies. She described his steady devotion and how “ordinary” love—showing up, staying present, holding the day together—became the center of everything. In many illness stories, a spouse becomes a supporting character. Tatiana made it clear that George was not an accessory to her narrative; he was the life she was losing.

That’s where the word “cheated” resonates. It is not poetic. It is blunt. It’s the language of someone who understands that being brave doesn’t erase unfairness. She could love her family and still feel robbed of the years she thought were guaranteed.

If you read her words closely, you also notice what she didn’t do. She didn’t turn her illness into inspiration content. She didn’t reduce it to a slogan about fighting. She wrote about staying present instead—trying, each day, to soak in what she could and to remember. That emphasis matters because it shifts the story from “winning” or “losing” to “being.”

It’s also why the public fixation on “final words” can miss the point. Her writing wasn’t a last performance. It was an act of witness. She documented what love looks like when it is forced to live beside fear.

So what about the funeral?

The public record, at least for now, has been sparse. There are reports that her family confirmed her death and expressed love, but details about services have not been widely shared. That silence can be interpreted in several ways, and it’s important to separate fact from assumption.

One possibility is simple privacy. Tatiana had two young children, and every public detail becomes permanent on the internet. A private service could be an attempt to protect them from growing up inside a searchable archive of their mother’s death.

Another possibility is that the family’s public profile makes discretion necessary. Even a small gathering can become a media event, and the Kennedy name has always drawn attention that families with different surnames don’t have to manage.

Some people have even speculated—again, without confirmation—that Tatiana might have asked for minimal public ceremony, preferring that her writing carry the weight instead of a public spectacle. That idea is plausible only because her essay was so intentional. But it remains speculation, and it’s worth holding it lightly.

What is not speculation is the central emotional contradiction Tatiana described: she wanted to protect her mother from grief, but she could not. She wanted to mother her children with her whole body, but treatment put limits on touch. She wanted to keep living the life she built with George Moran, but time was no longer something she could bargain for.

Those contradictions are the real “details.” They are the pieces that make people feel like they know her, even if they never met her.

There is also a larger question hovering over the story: why did so many readers respond as if they had been personally addressed?

Part of it is the writing. Tatiana didn’t speak in generalities. She wrote in specific fears, specific loyalties, specific love. She made the reader feel the weight of trying to be “good” for a parent, which is a surprisingly common burden. People outside famous families do it too: the daughter who tries to be easy so her mother can breathe, the son who hides problems so his parents won’t worry, the sibling who becomes the “reliable one” because the family can’t handle more chaos.

Tatiana named that dynamic at its most extreme: she was dying and still thinking, first, about the pain her mother would feel.

That’s not a Kennedy thing. That’s a human thing.

There is another reason Tatiana Schlossberg’s essay stayed with people: it sounded like it was written for two clocks at once. One clock was public time—the news cycle, the curiosity, the impulse to ask for “updates.” The other clock was intimate time—the minutes measured by a child’s nap, a spouse’s hand on a hospital rail, a mother’s worried phone call.

That double clock explains why many readers experienced her piece as both journalism and a kind of letter. She was describing reality, but she was also leaving a trace. For parents facing terminal illness, leaving a trace can matter as much as leaving money. A trace is what your children can return to when they are old enough to ask, “What did she sound like? What did she love? What was she trying to hold on to?”

Publishing publicly also creates a tension: your most private fears become part of a public archive. Some people will argue that grief should stay inside a family. Others will say honesty helps other families survive their own crises. Tatiana didn’t resolve that debate; she simply chose, and accepted the cost.

And because her diagnosis came after giving birth, the essay also underscores something many people forget: postpartum life is already physically intense. Add a sudden leukemia diagnosis and treatment, and the word “present” stops being philosophical. It becomes the hardest daily job.

That may be why her pages feel less like closure and more like a hand out.

Another reason the story resonates is timing. She revealed her diagnosis weeks before her death. That compresses the reader’s experience: you meet her voice in crisis, and then you are told she is gone. There isn’t enough time for the public to acclimate, to make the story feel distant. It stays close.

And because Caroline Kennedy’s life has been defined by public memory, Tatiana’s essay also functions as a message about legacy. It suggests that legacy is not only what you achieve. It is what you refuse to hide. It is the honesty you leave behind when you can’t control the outcome.

That’s why her “final words” feel heartbreaking. They weren’t a quote designed for history books. They were a plain fear: that her mother would have to endure another tragedy. That fear alone carries generations of grief in a single breath.

It also reframes how people think about Caroline Kennedy. Public figures are often treated as symbols, and symbols are expected to withstand anything. Tatiana’s writing pulled her mother back into the category of human: someone who has already lost too much, someone whose daughter spent her whole life trying not to add to that list.

The story also reframes how people talk about illness. It is easy to romanticize survival narratives and ignore what treatment actually does to daily life. Tatiana didn’t let readers do that. She described the costs in domestic language: diapers, baths, feeding, the tiny acts that make up a parent’s day. That makes the loss feel real, not abstract.

There is no neat takeaway that can respect this story. But there are a few truths that people keep carrying away from it.

One: love is not always comforting. Sometimes love is the reason a diagnosis hurts more, because love expands the number of people you worry about.

Two: the hardest grief is sometimes anticipatory. Tatiana was grieving what she would miss while she was still here, and that kind of grief is exhausting.

Three: being “strong” does not mean being cheerful. Her strength was her willingness to tell the truth without smoothing it.

If you’ve ever watched someone you love go through serious illness, you know that the public side of grief is almost always wrong. People ask for updates and closure. Families live in half-days and changing lab results. Friends want inspiring messages; caregivers want a nap. A public story can never capture the texture of those weeks.

Tatiana’s writing got closer than most, because she wasn’t trying to teach. She was trying to remember.

And now that she has died, readers are left holding the same question she held: what do you do with time when you realize it is not guaranteed?

Some people will answer with goals. Some will answer with work. Her essay points to a quieter answer: presence. Soaking in what you can. Naming love out loud. Saying what matters before the chance disappears.

If her family chooses a private funeral, that privacy will probably be misread by some as secrecy. It may simply be protection. And in a story that is already heavy with the theme of protection—Tatiana trying to protect Caroline, trying to protect her children, trying to protect her marriage from the unstoppable—it would make sense that her loved ones would want to protect what remains.

In the end, the most respectful way to hold this story might be the way Tatiana held her own life in those final weeks: without spectacle, without pretending, without turning pain into branding.

A daughter who worried about her mother.

A wife who loved her husband.

A mother who wanted her children to remember her.

A writer who refused to look away.

That is enough.

And if you feel changed after reading about her, maybe the simplest response is the one she kept circling back to: call the people you love, hold them closer, and stop assuming there will be more time tomorrow.