kk.When “Breaking News” Meets a Family’s Grief: Caroline Kennedy’s Loss Without the Rumors

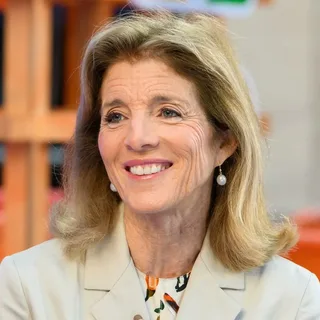

Caroline Kennedy has spent most of her life living inside a contradiction. She was born into a family whose faces became part of America’s permanent memory, yet she grew into an adult who guards her private life with near-iron discipline. She rarely grants interviews about grief. She almost never narrates her own pain. And still, when tragedy touches her family, it does so in front of an audience.

That tension was visible again on Monday, January 5, in New York City, when members of the Kennedy family gathered for the funeral of Tatiana Celia Kennedy Schlossberg, Caroline’s daughter. The service itself was private, but the fact of it was public, because the Kennedy name pulls cameras and commentary the way gravity pulls tide.

For Caroline, now 68, the day was not a “story” so much as the newest and most personal chapter in a lifetime shaped by loss. Tatiana was 35. She left behind her husband of nine years, George Moran, and two young children: Edwin, 3, and Josephine, 18 months. In any family, a death like that would be devastating. In this family, it also arrives with echoes.

As historian and Kennedy biographer Steven M. Gillon told People, “Whenever a Kennedy dies … it just brings to mind all the others.” His point was not that tragedy is contagious, or that fate is at work. His point was about memory. One funeral pulls previous funerals forward; one headline makes earlier headlines feel newly present.

Tatiana’s final months became widely known because she chose to write about them. In November, she published a New Yorker essay that described her diagnosis and her treatment with clarity, discipline, and a kind of tenderness toward the people who loved her. The essay placed her illness in the center of ordinary life: a mother, a marriage, two children too young to understand what was happening.

Five weeks after that essay appeared, her family announced that she had died on December 30. The statement was brief and direct, the kind of sentence families use when they have no language large enough for what happened. Grief was named without ornament.

For Caroline, Tatiana’s death is not only a loss in the present. It is also a reminder of how long her family has lived with public mourning. In Gillon’s telling, the most striking element is the contrast between Caroline’s temperament and the scale of what the world expects to witness. She is, he said, “an incredibly private person” facing “a very public tragedy.”

That contrast is part of why so many people reach for easy labels. “Kennedy curse” is an old phrase, and it always resurfaces after a new death. It is the kind of shorthand that travels quickly online because it compresses complexity into a single dramatic idea. But it can also flatten the humans inside the story, as if grief were a plot device instead of a life.

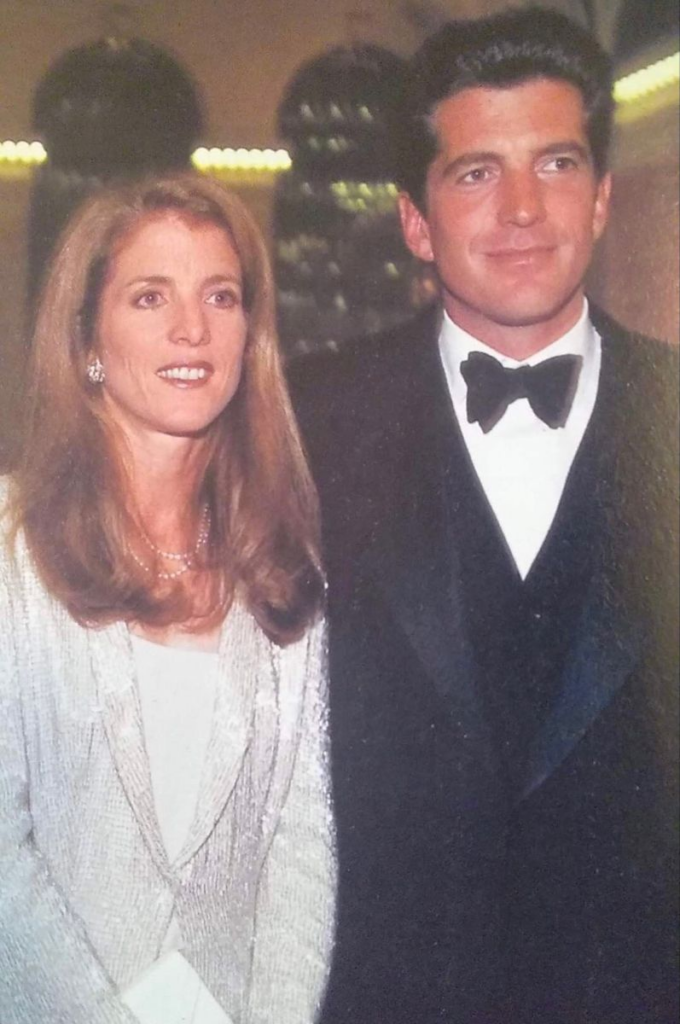

Gillon’s comments push in the opposite direction. He emphasizes the lived reality of shared losses, especially the bond between Caroline and her brother, John F. Kennedy Jr. Friends, he told People, have long said that if anyone understood Caroline, it was John—because he suffered the same early tragedies.

Caroline and John were shaped by the same childhood rupture: the assassination of their father, President John F. Kennedy, in 1963. Caroline was five, old enough to recognize that something irreversible had happened and old enough to see her mother’s grief on the surface of daily life. John Jr. was younger, but he grew up inside the same absence, surrounded by the same public fascination.

After the assassination, Robert F. Kennedy became a substitute father figure for both children. He was the uncle who stepped closer, who tried to provide steadiness, who embodied a living connection to the lost president. Then, in 1968, Robert Kennedy was assassinated too. For Caroline, it was another message that death could arrive without warning, in public, by violence. For John, it was another hole in the family’s structure.

By the time they were adults, both siblings carried a shared history that very few people could understand from the inside. They were not just the children of famous parents. They were children whose losses were repeated in documentaries and anniversaries, whose private moments were preserved in iconic photographs. The world remembered John Jr. saluting his father’s coffin. Caroline remembered what it felt like to be watched while grieving.

That is why, in Gillon’s view, the brother-sister bond mattered so much. They could talk about childhood without translating it for anyone else. They could share a memory without worrying that it would become a headline. They could understand each other’s silences.

Gillon’s work on John F. Kennedy Jr. returns to one idea: he never fully accepted the part the public wrote for him. John carried the charisma people wanted to believe in, but he resisted becoming a permanent symbol. That resistance mattered to Caroline because she shared it. Both siblings understood fame as a second job, a daily negotiation over where the “public” ends and the “self” begins. When John was alive, Caroline did not have to explain that pressure; he already knew it from the inside.

Outsiders tended to cast them as opposite halves of a legend—John as the charming heir and Caroline as the serious guardian of the family name. Real life was less tidy. Caroline’s privacy was quieter, John’s was more complicated, but both were shaped by the same childhood lesson: attention can distort love into a kind of ownership. Their bond was not only affection. It was shared strategy.

That is why the period after Jackie’s death, and then after John’s, can be understood as a narrowing of safety. Jackie had been a human boundary, someone who could say “no” to the world and mean it. John had been a personal boundary, someone who could share the weight without being asked. When both were gone, Caroline’s solitude inside the public story deepened.

Tatiana’s death arrives in that context, and it forces Caroline to manage visibility again. A funeral is a family ritual, but for a famous family the ritual becomes a public event even when no one invites the public in. The questions come quickly: who attended, what was said, what did it “signal.” Those details are not the point, yet they can dominate the conversation because celebrity culture is trained to read real grief like fiction.

Caroline’s instinct has usually been to give the public as little as possible. She understands ceremony, but she keeps personal emotion off the record. That does not mean she is cold; it means she is disciplined. Tatiana’s essay complicated the pattern by giving readers an unfiltered voice: a daughter who loved her mother and feared adding worry. After Tatiana died, Caroline returned to the family’s traditional posture—brief words, controlled light—not to tease the public, but to protect the living.

Then Caroline lost that understanding.

On July 16, 1999, John F. Kennedy Jr. died when the small plane he was piloting crashed into the Atlantic Ocean. He was 38. His wife, Carolyn Bessette, was 33. Her sister Lauren was 34. The search and the coverage became a national fixation. In the public mind, the tragedy carried the familiar weight of the Kennedy name. In Caroline’s life, it carried something quieter and sharper: the only person who had truly shared her entire arc was gone.

This is the line Gillon draws when he says Caroline “suffered the same losses that John suffered, except that she also suffered the loss of her brother.” They began with the same tragedies, but she lived beyond him. She became the lone surviving child of John and Jackie Kennedy, the sole direct witness left to their particular family story.

That status is often described like a statistic, but it functions like a pressure. It means that every time the public returns to the Camelot era, there is one living person who has to feel that history not as myth but as memory. It also means that Caroline’s personal grief is repeatedly treated as public property.

The loss of their mother deepened that pressure. Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis died in 1994 at age 64, which many people described as young. For Caroline and John, it meant losing the parent who had built the boundary between their family and the world. Jackie had tried to create normalcy around two children who could never fully escape attention. When she died, her children became the primary guardians of their own privacy.

After 1994, Caroline and John were not only siblings; they were also co-keepers of a family’s intimate history. When John died in 1999, Caroline inherited that role alone.

Now, after Tatiana’s death, the story moves into a different category of grief. Losing parents, even violently, fits a terrible but recognizable order of life. Losing a sibling breaks a different piece of the self. Losing a child overturns the order entirely.

That is why Gillon says Tatiana’s death “may be the hardest of them all.” It is not a competition among tragedies. It is an acknowledgement of how grief changes when the future is the thing that disappears. A parent expects to protect a child. A parent expects, at minimum, to witness a child’s adulthood. When that expectation is shattered, the world no longer feels arranged correctly.

Tatiana’s own writing hinted at this reversal. In her essay, she described not only the medical facts but the emotional calculus of a daughter who had spent her life trying to protect her mother from pain. She wrote about wanting to be a good student, a good sister, a good daughter, and about trying not to make her mother upset. The detail resonates because it reverses the usual parental instinct: the child trying to shield the parent.

And then, despite that instinct, Tatiana’s death adds a new wound to Caroline’s life. It arrives after decades of losses that have already trained her in how to stand at funerals, how to keep her face composed, how to hold grief without letting it spill into spectacle.

Yet training does not make a person immune. It only teaches a person how to move while carrying weight.

The People story emphasizes how little the public truly knows about Caroline’s interior world. Gillon makes the point directly: we can document the tragedies, but we cannot document exactly how she processed them, because she has not talked about them publicly. Caroline’s silence invites speculation, but speculation is not evidence.

What outsiders can see is a pattern of restraint. Caroline has tended to respond to public grief by making her public presence smaller, not larger. She does her official duties. She shows up when it is expected. She does not build a personal brand on vulnerability. Even when she has served as a diplomat, she has been careful about turning herself into the story.

That choice reads differently to different people. Some interpret it as strength. Others interpret it as a strategy for survival. Both can be true at the same time.

Gillon suggests that Caroline’s approach fits a larger Kennedy family tradition: meeting death with resolve. Resolve can look like steadiness, like showing up, like refusing to collapse in public. But resolve also has a darker edge. It can mean living with pain because there is no alternative. It can mean taking one breath and then another, because the world does not stop for anyone, not even for a famous family.

At Tatiana’s funeral, resolve would have been present in the simplest details: walking through a city street, entering a service, facing relatives, facing the knowledge that everyone outside the room was curious. According to People, multiple generations of Kennedys attended, which suggests both community and continuity, a family gathering to support one another even while being watched.

The scrutiny is part of what makes this grief unusual. When a family is famous, the public tends to treat tragedy as a narrative with meaning. People ask who attended, who did not, what was said, what it implies about politics, about family dynamics, about history. But those questions can feel disrespectful when the central fact is simple: a woman lost her daughter.

This is the moment where the “private person” versus “public tragedy” contrast becomes more than a phrase. Caroline’s instinct is to keep family matters inside the family. The world’s instinct is to pull the Kennedy story outward, to place it on screens and timelines, to connect it to everything that came before.

In practice, that means Caroline’s grief is never only hers. It becomes a mirror for the nation’s memory of 1963, of assassinations, of lost promises. It becomes a trigger for older Americans who remember the funeral images, and for younger Americans who know those images only as history lessons. The death of one young woman becomes a portal into sixty years of cultural memory.

But for the people in the funeral pews, it is not cultural memory. It is personal loss. It is George Moran learning how to be a widower. It is two children growing up with a mother who will be present through photographs and stories rather than through daily touch. It is Caroline facing the fact that the person she raised, the person she watched become an adult, will not be there for future birthdays, graduations, or ordinary mornings.

It is also Caroline’s recognition that the one person who understood her earliest losses is not there to help her interpret this new one. John Jr. once served as her closest witness, the sibling who could look at her and understand without explanation. That role cannot be replaced by friends, no matter how loving, because no friend shared the same origin.

Now Caroline stands with two kinds of absence: the absence of her parents and brother behind her, and the absence of her daughter ahead of her.

As grief piles up, people sometimes imagine that the bereaved become numb. In reality, grief often becomes sharper, because each new loss calls earlier losses back. This is what Gillon means when he says you cannot look at a Kennedy death in isolation. The family’s history makes every death feel connected, even when the causes are different.

Tatiana’s story also highlights the way a family’s public role can intersect with medical reality. Her essay described the brutality of a cancer diagnosis and the long sequence of treatment and uncertainty. The public read it because of her name, but many stayed with it because of the honesty of her voice. In that sense, Tatiana did something rare in the Kennedy context: she offered a direct account of suffering rather than a carefully managed statement.

And then, after her death, the family returned to the traditional style: brief, formal, protective.

That return is not hypocrisy. It is an illustration of different needs. A young writer can decide to narrate her illness. A grieving mother may decide to say as little as possible, because words can invite intrusion. Caroline’s privacy is not only a preference; it is a boundary that keeps her functioning.

The People article leaves readers with a sense of mystery around Caroline. She is a “beloved presidential daughter” and a “steady diplomat,” yet she is also someone who keeps her emotions largely hidden. Gillon notes that we can only surmise how she deals with tragedy, and he suggests that she does it through resolve.

There is, however, another practical reality that follows Tatiana’s death: the work of keeping a memory alive for children who are too young to remember clearly. Caroline knows this work intimately because her own mother did it for her after JFK’s assassination. Jackie had to preserve a father’s presence through stories, rituals, and careful curation of memory.

Now Caroline may find herself doing something similar for Edwin and Josephine. That work is quiet and repetitive, not dramatic. It happens in living rooms and kitchens, not in press releases. It happens when a child asks, “What was she like?” and the adults choose words that will comfort without lying.

In families marked by public tragedy, that work also involves protecting memory from distortion. It means preventing a mother from becoming a headline in a child’s mind. It means giving the children a full human picture: their mother as a person who laughed, who wrote, who cared about the world, who loved them fiercely.

This is where the public should be careful. It is easy to consume famous grief as a spectacle. It is harder to remember that grief is ongoing labor for the living, especially when children are involved. The news cycle ends. The family’s real life does not.

Gillon’s central claim—that John Jr. was the only one who truly understood Caroline’s losses—lands with extra force in this moment because it highlights the loneliness inside the famous story. Caroline has siblings only in memory now. The person who shared her first grief is gone. The daughter who carried the future is gone. The circle of shared understanding is smaller than most people can imagine.

None of this requires a curse to explain it. It requires only time, loss, and the unusual pressure of living under a national spotlight.

What remains, beyond the headlines, is a private woman walking through a public world with as much control as she can manage. She will almost certainly continue to say little, to protect her family’s space, and to keep going in the way she always has.

And somewhere, beyond the attention, there will be two small children growing up. They will learn their mother through stories and through the love of the people who knew her. Caroline will help shape those stories, not for the public, but for them.

In that quiet work, the Kennedy legacy becomes less about Camelot and more about endurance: the decision, after each loss, to keep memory honest, to keep love present, and to keep living.

In the months ahead, her grief will stay private, but her daughter’s words may keep opening a door to compassion again.